Winter weather in Tokyo is generally bright, clear, and pleasant. February 8, 1982 was no exception.

As JAL Flight 350 went into its final approach to Tokyo’s Haneda Airport, the 166 passengers on board had a view of a brilliant blue sky arching above the placid waters of Tokyo Bay. It was hard to imagine more perfect flying conditions.

As the passengers prepared for landing, their thoughts started turning to the day’s business: appointments, subsequent connections, soon-to-be-reunited loved ones, and other matters.

Just a few short minutes more, and they would be on the ground.

JAL Flight 350 was a McDonnell Douglas DC-8, a four-engine narrow-body airliner, similar to the Boeing 707, carrying 166 passengers and a crew of eight.

Piloted by Captain Seiji Katagiri, Copilot Yoshifumi Ishikawa, and Flight Engineer Yoshimi Ozaki, Flight 350 had departed Fukuoka at 7:34 a.m.

The 90-minute flight to Tokyo had been uneventful, which is expected for a flight on one of the world’s safest airlines along a route that today is flown daily more than 30 times each way.

The big jet lined up with the approach light towers that extend out from the end of runway 33R into the shallows of Tokyo bay. Everything about the final ILS (Instrument Landing System) approach was routine and by the book.

Suddenly, while the massive DC-8 was only 165 feet above the water and a few short minutes from touchdown, Captain Katagiri reversed two of the jetliner’s engines and pushed the control column fully forward, putting the plane into a dive.

Flight Engineer Ozaki jumped up from his seat and attempted to grab the captain.

Copilot Ishikawa cried out, “What are you doing?” and attempted to pull back on the control column.

But at this low altitude, all attempts to save Flight 350 were in vain.

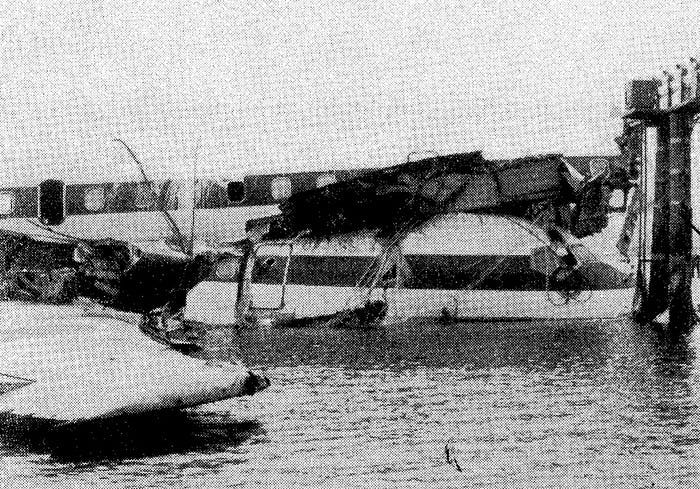

The aircraft plunged nose-first into Tokyo Bay a thousand feet short of Runway 33R, impacting a light tower that sliced into the fuselage immediately behind the cockpit. This caused the cockpit section to break off and come to rest in the shallow water as everything behind it continued to rush forward.

The fuselage eventually came to rest on top of the cockpit section. One Japanese news outlet reported that all of the 24 killed and those seriously injured in the crash were seated in the front 11 rows of the passenger compartment, as they were crushed by the weight of the onrushing fuselage.

But things could have been much worse. Since the crash occurred so close to Tokyo’s Haneda Airport, more than 500 rescue workers quickly arrived on the scene. This rapid response was credited as one of the reasons the crash’s death toll was relatively low.

Even so, complete evacuation would take eight hours due to delays caused by the need to pump the remaining fuel from the plane to reduce the risk of fire and explosion. Another factor hampering rescue efforts was the need to ferry passengers to land by boat.

One of the first survivors pulled from the cold waters of Tokyo Bay to safety was a man claiming to be a passenger on the way to Tokyo on business. The self-identified businessman had sustained injuries to his back and internal organs, so he was taken to a nearby hotel for treatment.

Later it was discovered that the injured businessman was none other than Captain Katagiri, who had ditched his pilot jacket and tie after the crash, and grabbed a sweater that apparently belonged to one of his unfortunate passengers.

When Katagiri was identified at the hotel, he was hospitalized for psychiatric evaluation.

Who is Seiji Katagiri?

Seiji Katagiri was born on June 10, 1946, to a wealthy family that owned a watch and clock shop in the Kyushu resort city of Beppu, in Oita Prefecture.

An exceptional student in high school, it is said that he could have easily been accepted to the prestigious Kyushu University. Instead, Katagiri opted to study at the Department of Mathematics, Faculty of Science, Okayama University.

After two years at Okayama University, Katagiri transferred to Japan’s Civil Aviation College, where he obtained his commercial pilot’s license.

In short order, Katagiri became a pilot for Japan Air Lines, a husband, and the father of a small daughter. He seemed to be on a fast track to enjoying all of the fruits of the Japanese dream. But everything in the Katagiri household was not as quiet and peaceful as it seemed.

A history of mental problems

According to testimony during his trial, Katagiri started to show signs of mental illness around 1976.

Police were once called to the Katagiri home because he was convinced someone was tapping his phone. There were no taps.

It got to the point that his wife became concerned for her own safety and temporarily left him. Following the crash of Flight 350, she reportedly told interviewers, “My husband just wanted to die.”

In November 1980, Katagiri was granted three weeks’ leave to deal with his deteriorating mental state. Diagnosed as suffering from depression and gastritis, Katagiri ended up being grounded for nine months. Following his leave, Katagiri was deemed fit to fly and was reinstated to the rank of copilot for three months and then back to pilot in late 1981.

The biggest red flag came just one day before Katagiri crashed Flight 350 into Tokyo Bay. On February 8, 1982, Katagiri was piloting a flight from Tokyo to Fukuoka with the same crew that would be with him the following day. Shortly after takeoff from Tokyo and without warning, Katagiri switched the right-hand engines to counterthrust, which could have sent the aircraft into a dangerous and deadly spin. It was only due to the quick thinking and action of Copilot Ishikawa that a nosedive was averted.

Katagiri turned to his copilot and said, “Well done.”

Was the incident reported?

Was a report ignored?

Was this treated as a training exercise?

No information is available to answer these questions.

Investigation and Trial

Since the weather was so good and there was no sign of mechanical failure, investigators turned their attention to the actions of the pilot and crew.

The only physical evidence investigators had to go on was the cockpit voice recording, which revealed Katagiri had cried out loudly during the landing. The next step was to question the other members of the flight crew.

The interview with Copilot Yoshifumi Ishikawa was difficult because he was hospitalized with severe injuries.

According to news reports, Ishikawa told investigators:

“Control column movement was extremely heavy, though it normally could be pulled up easily. I thought the captain had done something wrong, and I shouted at him. It all happened so quickly that I don’t really remember what I said. I was so absorbed in trying to pull up the control column I did not notice what the captain was doing.”

When investigators talked with Katagiri, he had little to say at first. Later, during his trial, he testified:

“When I switched from autopilot to manual operation in order to land the aircraft, I suddenly felt extremely queasy. I was then overcome by an inexplicable panic and then almost fainted.”

Katagiri was eventually arrested on the charge of professional negligence resulting in fatalities.

At his trial, it was found that Katagiri had deliberately crashed his plane in a suicide attempt, but he was declared not guilty by reason of insanity. He was committed, under Japan’s Mental Health Law, to the Tokyo Metropolitan Matsuzawa Hospital for life. There, Katagiri was diagnosed as suffering from paranoid schizophrenia.

After some years of treatment, Katagiri was declared no longer a danger to himself and society and released.

Conclusion

The Japanese government conducted an investigation and released a 246-page report that placed partial blame for the crash on the medical system that allowed Katagiri to go back to work as a pilot too soon.

Japan Airlines set up a committee to review “both the physical and mental health of flight crews to ensure safe flight operations.”

Seiji Katagiri is widely reported to be currently living a comfortable life with his wife near Mt. Fuji, supported by a generous pension and the wealth of his family.

There also have been rumors that Katagiri is divorced from his wife, confined to a wheelchair, and living near a facility for the mentally handicapped in Kanagawa, Japan.

Japan has strict laws protecting the private information of individuals. Since Katagiri was found to be innocent by reason of insanity, very little information about him is available in the public domain.

This story originally appeared on Medium.